Lead Author: Laia Pibernat-Mir

Additional Author: Cristina Moreno

Organizations: Farmacèutics Mundi Catalunya and Medical Anthropology Research Center, Universitat Rovira i Virgili

Country: Spain

Abstract

Universal access to essential medicines represents one of the clearest contemporary challenges to the exercise of the right to health due to the limitations that linking the development and marketing of the drug with the private sector entail. Often, medicine ends up being a hijacked right, only within reach for those who can pay. In the framework proposed by the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, there is an obvious need to open the discussion about plausible solutions to achieve this right to health within the legal framework of innovation, development and distribution of medicines and health. We argue from the academic and the activist areas that this has to be a transdisciplinary discussion.

Medical Anthropology Research Centre (MARC) of Universitat Rovira i Virgili and Farmacèutics Mundi Catalunya, are proposing the International Conference “Medicines and Culture” as a space and environment to promote a discussion that incorporates players from multiple sectors, which includes the spheres of academia, politics and civil society, which gives cause for the creation of alliances and dialog that can cut through contradictions between various laws, public health policies and the social realities of the subjects in a global manner. Beyond the meeting days, the “Medicines and Culture” Conference is planned as a source of publications, information and various communication tools with which to disseminate the most prominent messages and most relevant aspects and conclusions of the conference. This proposal requests support, on the one hand, to strengthen the presence of academic and activist experts on the international level in order to involve in the dialog the principal players in the global discussion, and on the other, to develop effective communication tools for the subsequent dissemination.

Submission

In the contemporary world, medicine holds a central position in public institutional agendas and international development agendas, and in the daily management of the processes of health, disease, care and prevention. Increasing institutional resolve to reduce the gap in access to medicines between populations is clear, however, it constantly represents one of the most prominent contemporary challenges to the exercise of the guarantee of the right to health. Linking the development, innovation and marketing of drugs with the private sector of large pharmaceutical corporations oftentimes transforms medicine into a hijacked right that is only within reach of those who can pay. In this framework, the role of the Agreement on Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) must be stressed, which takes into account inconsistencies between international trade standards and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. To it is added that despite having ratified the international charter of human rights, most of the signatory states, which have obligations, often do not develop public joint financing policies that guarantee access to essential treatments for disadvantaged populations.1

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights drafted and signed in 1948 by all member states of the United Nations Organization recognizes in Article 25 the right to enjoy the highest level of health. Since then, one has observed the transectorial importance of guaranteeing said right, in order to guarantee fulfillment and enjoyment of the remaining universal human rights, as well as succeeding in the fight against poverty, in support of sustainable and equitable development of all human societies. In 1966, the detailed definition of the exercise of the right to health was drafted, as appears in Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). In 2000, the rapporteur committee added Comment No. 14, which develops the normative substance of the right, the obligations associated with it and measures required for its compliance. The Availability, Accessibility, Acceptability and Quality normative framework for compliance with the right to health, which is recognized in Comment No. 14 of the ICESCR proves to be highly applicable in the context of universal access to essential medicines.

Following the in-depth discussion at the 2015 Social Forum concerning access to medicines, we consider this an entirely appropriate time to continue to promote both dialog with respect to this question, and the pertinent changes that can help adapt and improve the consistency of national and supranational policies and legislation that concern access to medicines so that they have a positive impact on global health. Year after year, revision after revision, there are increasingly more arguments that emphasize the role of social determinants in access to health and essential medicines. In late 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals were signed, explicitly clarifying as well as designating a place for this discussion within the Post-2015 Development Agenda: the importance of promoting research and development of medicines and providing universal access to affordable essential medicines, as agreed in the Doha Declaration and with the flexibilities stipulated in the TRIPS.

In this current context, both academic communities and organized civil society (nongovernmental organizations), as the parties responsible for the right to health, must promote this right and specifically promote equitable access to essential medicines for the populations of the Global South whose right to health is systematically violated at this time. That is, we have the duty of playing a prominent role in condemning the lack of guarantee of the right, and defending and promoting civil and academic initiatives that offer responsible alternatives, as well as strategies with political impact to push our states and parastatal bodies to exercise their role as holders of obligations.

Given the response to the gap in access to medicines, and its link to the social determiners of health, on November 14, 15 and 16, 2016, the 2nd Conference of the Medical Anthropology Research Centre (MARC-URV) called “Medicines and Culture” will take place in Tarragona. The Conference is organized within the framework of the project “GenereM Salut Global” research, education and social transformation to promote women’s right to health” coordinated by Farmacèutics Mundi Catalunya with the collaboration of MARC and the Department of Anthropology, Philosophy and Social Labor of Universitat Rovira i Virgili (Tarragona, Spain).

The principal objective of the “Medicines and Culture” Conference is to promote interdisciplinary research of access to medicines in the globalized world, focusing primarily on the socio-cultural determinants and lack of access policies, as well as the creation of meeting and dialog spaces between the different social players involved. There are plans to discuss these aspects at the Conference, from the excellent opportunities that applied anthropology and social sciences can contribute, and under an interdisciplinary perspective, in order to understand the contemporary processes that contribute to difficulties in equitable access to medicines, and therefore, to health. From the socio-cultural perspective of this field of research, medicine is considered an object and a symbol; so that the chain of production, distribution, sale, prescription, use and consumption of medicines is influenced by these two dimensions: the material and the symbolic. All of these issues are the foundation of the Conference and the invitation to reflect on the contemporary challenges and dilemmas that the use of medicines in the globalized world entails.

Participation is open to researchers from a variety of academic disciplines who conduct interdisciplinary and/or transdisciplinary work on the aspects indicated, as well as members of organized civil society and/or user groups and/or activists who defend the right to health, and defend equitable access to essential medicines specifically. They are all invited to collaborate in the Conference days by presenting communications concerning relationships between medicines and cultures in their broadest sense, thereby contributing to the creation of knowledge and a discussion on the relationship between drugs and human behavior, and as a result, inevitable socio-cultural behavior in the context of global access to medicine.

We recognize the immense benefits that creating these discussions on the use and access to medicine in a transdisciplinary manner can bring, and not only in the academic framework. The collaboration between Farmacèutics Mundi Catalunya and the Medical Anthropology Research Centre (MARC-URV) as it is shows the coordination between both fields of research and discussion in the same context: civil and academic.

In this framework of promoting critical and informed citizens with respect to infringement of the right to health, at the same time as it aims and is oriented toward [its] condemnation and the creation of processes guaranteeing the right, the project has the following objectives:

• To learn and inform about the structural causes that provoke inequalities, specifically those related to socio-cultural and political structures that lead to infringement of the right to health in the Global South, more specifically with respect to the lack of access to essential medicines.

• To broaden understanding and social awareness of the joint responsibility we have as citizens of the Global North in these inequalities and infringement of the right to health in the Global South.

• To create areas for participation, dialog, involvement and alliance for the joint defense of violated rights, with and for various social groups with a key role in the process of social transformation: the university and national and international academic community and civil society organizations of both the North and Global South.

• To disseminate among the general citizens the principal discussions and conclusions carried out in the transdisciplinary participation areas, expanding the fundamental messages of awareness and impact with respect to the current situation of access to essential medicines in the world, and more specifically in the Global South.

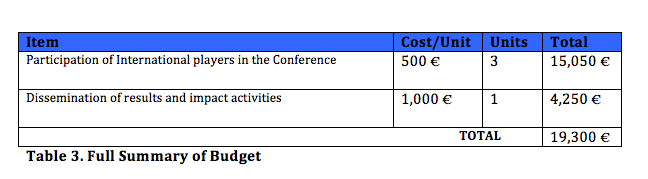

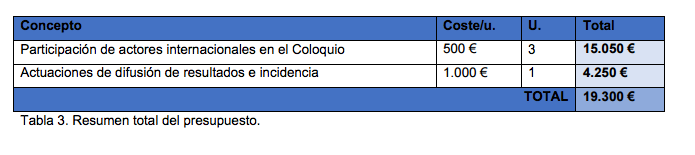

Through all this, support for this project will mean encouraging the meeting of players from the North and the Global South with the explicit push indicated above of the participation of players from both academia and organized civil society from the Global South, who could not through their own means attend or participate in the Conference. In this respect, in order to maximize the diversity of the participation and facilitate the involvement of international players, we propose inviting 10 players from Asia, Africa, America and Europe. To cover the costs, economic assistance is requested from the United Nations High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines. The estimated costs are presented below:

The Conference will be developed around six themes: (1) History of the medicine-culture relationship and appropriation of drugs and their dominance from the Hippocratic Doctrine to the present. (2) Determinants and socio-cultural consequences of access to medicines, considering the entire cycle of the medication (from production to consumption). (3) Race relations as a determining and/or differential factor for access to medicines, and consequently, health. (4) Activism and Medicines: The role of NGOs, civil society and social and grassroots movements for the agenda of access to essential medicines as a basic human right. (5) The role of legislation and intellectual property: free trade agreements, patents, generic medicines and the political economy of medicine. (6) Bioethics and pharmacological research: experiments, responsible use of medicines, protocols for research with humans and animals. The main questions to be addressed can be consulted on the Conference website.

The call for proposals is open not only to summaries for oral presentations, but also to photography samples, audiovisual compositions and posters. Similarly, other exhibition proposals will be evaluated as well as the presentation of workshops. The Conference will also accept a parallel sample of films focusing on the social role of medicines “Medicines in Film” and in which documentaries produced by Farmamundi will be viewed, and all audiovisual proposals received by the organizing scientific committee may be included. With this, the objective is to open dialog between different sectors of society and allow this to be presented in different formats, thereby opening the meeting to the integration of different languages, knowledge and communication, which enrich the discussion and debate to the fullest.

Following the Conference, strategies have been planned for disclosing the discussions in order to extend the communication that occurred there beyond the persons and organizations that participated in the meeting. It is thereby intended to bring the questions addressed to public, national and international debate, at the same time as carrying out actions with political impact that pressure signatory states to fulfill their role as holders of obligations with respect to the right to health and specifically compliance with the guarantee of equitable access essential medicines as the fundamental way of exercising this right. In this line of action, the following were planned: (1) Joint publication by Farmamundi and MARC-URV of a digital publication that will compile the most outstanding talks and discussions, which may include complementary items of experts who could not participate directly in the Conference and whose contributions complement and enrich the discussions held. (2) Production of video capsule summaries with the most outstanding talks and/or discussions as well as interviews of Conference participants. (3) Creation of an animated video and its dissemination through a viral company via social networks that shows in a concise and attractive manner the main messages condemning infringement of the right to health and the defense and promotion of universal access to essential medicines, according to the conclusions of the discussions held at the Conference.

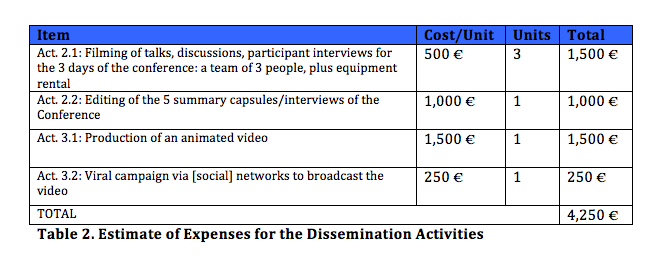

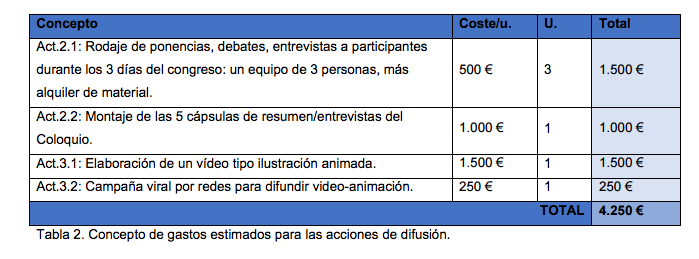

The project underway has planned the cost of the first of the activities (digital publication). In order to carry out activities (2) and (3), support is requested from the UN High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines to cover the following estimates:

As parties responsible for the right to health of the populations of the Global South for whom it is not guaranteed, MARC-URV and Farmamundi are involved in a process of integrating policies to improve access to medicines. We believe that support from the UN High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines could make this an outstanding opportunity to create alliances, build and/or strengthen networks for research, communication, information and activism on the international level to defend the right to health in general, and defend universal access to essential medicines in particular, thereby strengthening the performance of the Post-2015 Agenda with respect to Goal 3 of the Sustainable Development Goals (“Ensuring a healthy life and promoting the well-being of all ages”). Finally, the discussion and materials arising in the context of the Conference enriches and strengthens the discussion with respect to new and yet to be established proposals and solutions of interest to the members of the UN High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines. The budget requested in this contribution proposal is summarized below.

Tables in original language for clarity

Bibliography and References

Costa Chaves, G., Fogaça Vieira, M, and Reis, R. (2008) Access to medicines and Intellectual Property in Brazil: reflections and strategies of civil society. International Journal on Human Rights 163

Ford, N. (2004) Patents, access to medicines and the role of non-governmental organisations. Journal of Generic Medicines: The Business Journal for the Generic Medicines Sector 1(2): 137-145

Hoen E., Berger, J., Calmi, A. and Moon, S. (2001) Driving a decade of change: HIV/AIDS, patents and access to medicines for all. Journal of the International Aids Society 14:15

Illingworth, P. (2006) The power of pills: social, ethical and legal issues in drug development, marketing and pricing. London: Pluto Press

Méndez, M. (2000) The face and effects of medicines: a socio-cultural analysis. Revista Venezolana de Sociología y Antropología; 10(29):513-538

Pogge, T. (2008) Access to medicines. Public Health Ethics 1(2): 73-82

Reynolds Whyte, S., van der Geest, S., Hardon, A. (2002) Social Lives of Medicines. Cambridge University Press

Sampat, B.N. (2009) Academic patents and Access to medicines in developing countries. American Journal of Public Health 99(1): 9-17

UN (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. May be consulted at: http://www.un.org/es/documents/udhr/

UN (1966) International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). Available at: http://www.ohchr.org/SP/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CESCR.aspx

UN (2000) General Comment No. 14 Article 12 of the Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

UN Summit (2015) Sustainable Development Goals. May be consulted at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/events/meetings/2015/un-sustainable-development-summit/en/

UN (2015) Access to medicines in the context of the right to health. May be consulted at: http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/SForum/SForum2015/OHCHR_2015-Access_medicines_ES_WEB.pdf

WHO (2008) Human rights, health and strategies to reduce poverty. Series of publications on health and human rights, No. 5. Available at: http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/HHR_PovertyReductionsStrategies_WHO_SP.pdf

WHO (2008) Rectifying inequalities in a generation. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44084/1/9789243563701_spa.pdf

WTO (1994) Agreement on Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). May be consulted at: http://www.wto.org

WTO (2001) Doha Declaration, relative to the Agreement on TRIPS and public health. May be consulted at: http://www.wto.org